In San Miguel de Allende, the application of paint to a wall is a widely popular form of artistic expression (a word for which we balked at coining in an earlier viabrevis posting [“Paper, Pen, and Ink, or, Up Against the Wall Writing”]). Shop signs, product logos, street names, portraits of La Virgen de Guadalupe (Mexico’s patron saint), and, relatively recently, American-style graffiti may all be seen on the city’s walls.

Not surprisingly, anticipation of Pope Benedict XVI’s recent visit to Mexico inspired a flurry of wall-painting activity as it did considerable coverage in the other media, not all of it enthusiastically welcoming. Mexico, after all, has had a long history of conflict over the boundaries between Church and State, the secular and the profane. Indeed, around the time of the Pope’s arrival, the national legislature was winding up a two-year debate on a constitutional amendment that would add the word “secular” (laica) to make explicit the definition of the Mexican state as a secular republic (una República representativa, democrática, laica…) while ensuring such human rights as the free exercise of religion (which opponents feared might open the door to teaching religion—specifically, Catholic doctrine—in the public schools or—ahem—holding religious services in public). On the other hand, Mexico’s population is overwhelmingly Catholic by tradition and current practice, and even for nonbelievers, a visit from a pope is a noteworthy event.

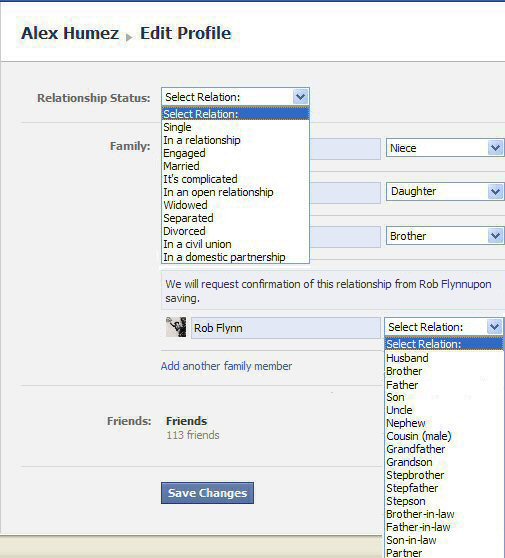

Two other events of recent and immediate history have helped to a greater or lesser degree to focus public expression on the papal visit. The first was the clerical abuse scandal involving the high-profile Mexican priest Marcial Maciel, the investigation of which, begun under Pope John Paul II, was closed not long ago by Pope Benedict XVI in a way that the victims and their families, by all reports, did not find satisfactory and were hoping (in vain) to meet with the pope to discuss during his stay. The second event (or nonevent) was the “quiet period” (known as the veda) during which all announced candidates running for president are barred from publically campaigning, which would include advertising in any of the conventional media or stenciling your party logo with an exhortation to vote for you on a wall. This period was due to end shortly after the Pope’s visit.

Here, then, is an example of a stenciled notification of the Pope’s imminent arrival:

Or, writ large:

The message “Ya viene el Papa” [‘The Pope is coming soon’] is pretty straightforward, and the resemblance of the squared circle enclosing the word “Papa” to the logo (soon to be ubiquitous) of one of the major political parties (PAN, the Partido Acción Nacional) is presumably coincidental.

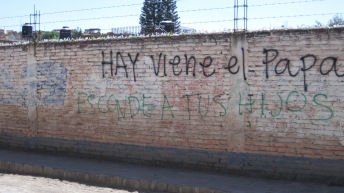

The following photo is of the part of the wall immediately adjacent to the one in Ya viene el PAPA (1):

“Hay viene el papa” [literally, ‘There is/are the Pope is coming’] contains a misspelling—a slip of the spraypaint can—possibly for the not quite homophonous “Ahí” (‘Here, Hither’), “Hoy” (‘Today’), or—and this is a bit of a stretch—“Ya” (“Soon,” as in the stencil). Take your pick (and say nothing about the schools). We may infer from the differently-colored paint that the grammatically and orthographically correct “Esconde a tus hijos” [‘Hide your kids’] is a response to the above.

While the reference to clerical sexual abuse is obvious in the response, it is worth noting that, while grammatically masculine in gender, “hijos” is semantically unspecific in this context: Like the other Romance languages, Spanish uses the grammatically masculine form (when there is one) as the default when referring to an aggregate that may contain members of both genders. Indeed, a cartoon that appeared in the newspaper Reforma during Benedict XVI’s visit showed a bishop whispering to the Pope “¡¿Y esos monaguillos?!” [‘And those altar boys?!’], referring to the presidential candidates of the three major parties (one of whom is a woman) depicted at the pope’s side dressed as, yes, altar boys.